Key takeaways:

- A little over 40% of parents did not know about the possibility of false-positive and false-negative results on newborn screening.

- Race/ethnicity and education level impacted understanding of newborn screening.

When asked about newborn screening tests, nearly half of surveyed parents with a young child did not know the conditions included on these tests, according to results presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting.

Susanna A. McColley

“We want families to know about newborn screening, to assure that infants with abnormal screening tests have prompt evaluation,” Susanna A. McColley, MD, FAAP, ATSF, professor of pediatrics in pulmonary and sleep medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, told Healio.

Data were derived from Heffernan ME, et al. Parents’ awareness, understanding, and experiences with newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. Presented at: Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting; May 2-6, 2024; Toronto, Canada.

“While the screening tests aren’t perfect (babies with abnormal screening tests often don’t have the disease of concern, and some babies will have a negative screen when they do have the disease), newborn screening tests for conditions that should be treated very early in life for the best possible health outcomes,” she said.

Using survey data, McColley and colleagues assessed responses from 1,596 U.S. parents with a child aged 0 to 12 years to find out what they remember and know about newborn screening.

As Healio previously reported, a CF diagnosis is often delayed or missed in nonwhite infants, so researchers made sure that self-reported race and ethnicity in this survey was similar to the make-up of the U.S. population, including white (61%), Hispanic/Latino/Spanish (19%), Black or African American (13%) and Asian (7%) individuals.

Findings

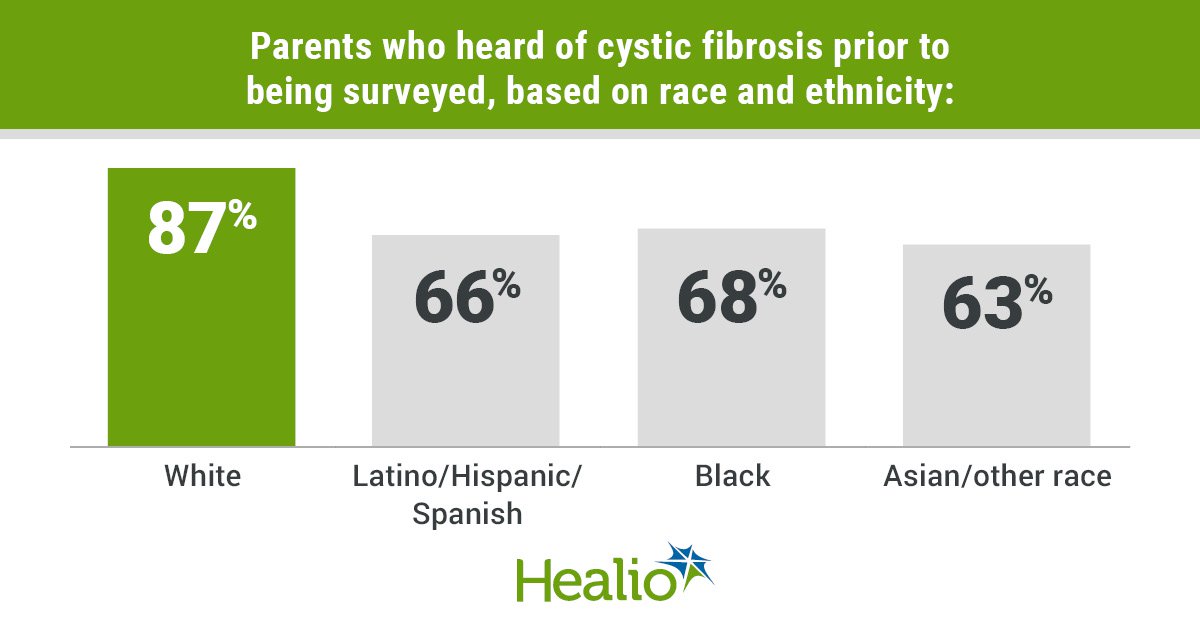

Prior to the survey, a majority of parents (79%) reported an awareness of CF. However, this significantly differed according to race and ethnicity, with more white individuals responding to this question in the affirmative (87%) than Latino/Hispanic/Spanish (66%), Black (68%) and Asian/other race (63%). Further, fewer parents with a high school education or less reported an awareness of CF vs. parents with a college degree or higher (72% vs. 81%).

When asked about the conditions screened for during testing, only 51% said they knew the included conditions. Based on race and ethnicity, significantly more Black and Asian/other race parents knew these conditions vs. white parents (58% vs. 61% vs. 48%).

In response to, “Did you know that cystic fibrosis is a disorder that can be detected with newborn screening?” 48% of the total cohort said yes. Based on education level, this answer was found more often among those with a college degree or higher (53%) vs. some college/technical school (45%) and high school or less (46%).

For the most part, knowledge about the possibility of false-positive (58%) and false-negative results (54%) was split down the middle of the overall cohort, according to researchers. Findings for these two questions did not significantly differ by race and ethnicity, but significantly more parents with a college degree or higher knew about false-positive results than those with a high school education level or less (62% vs. 56%).

Remembrance of newborn screening following birth was reported by 75% of respondents. Between those with a college degree or higher and those with high school education or less, a greater proportion of parents with higher education recalled screening (78% vs. 72%).

The difference between white and Latino/Hispanic/Spanish parents for this question was also significant (75% vs. 76%; P = .02).

Based on the whirlwind that follows the birth of a child, Marie E. Heffernan, PhD, assistant professor in the department of pediatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and another author on the study, was not very surprised by this finding.

Marie E. Heffernan

“The first few days after an infant is born there is so much going on for parents, plus they are sleep-deprived, and trying to navigate all that comes with having a newborn,” Heffernan told Healio. “This is especially true for first-time parents. It makes sense that parents may not remember details about the newborn screening process during that period.”

When responding to, “Did a health care professional talk to you about the reason for doing a newborn screening test on your youngest child?” more parents responded yes vs. no (60% vs. 17%), but 23% did not remember.

Researchers also found that significantly more Black vs. white individuals responded yes to the above question (68% vs. 58%).

In reaction to the survey findings, McColley told Healio she was not surprised by the general lack of understanding about newborn screening.

“I and many other parents I know don’t remember much about their children’s newborn screening, even though the first newborn screening test was first implemented in the early 1960s,” she said. “I have also met families who were surprised that their babies were tested for a condition without their explicit knowledge or consent.”

Abnormal screening results

Within the total cohort, 447 parents had a child with a positive screening test, and difficulty understanding test results was commonly expressed by this group (75%).

Researchers also asked this set of parents about how they felt after receiving the news of a positive newborn screening test. In response to the statement, “I felt supported by my child’s health care team,” 34% strongly or somewhat disagreed.

Further, 50% strongly agreed to being worried for their child, 30% strongly agreed to feeling sad/depressed and 25% strongly agreed to feeling lonely/isolated.

“We saw that parents in our study reported feeling worried and sad, but they also reported feeling hopeful and supported by family and friends,” Heffernan said. “Understanding how parents manage the emotional aspects of the newborn screening could help us learn how clinicians can better support families through this process.”

Both the reports of difficulty understanding positive screening results and a lack of support were somewhat surprising, according to McColley.

“[It should be noted,] many newborn screening tests are for disorders that are quite rare and require additional testing and evaluation from a specialist,” she said. “As with any abnormal screening test, the time from notification of a possible problem to getting a diagnosis confirmed or excluded can be emotionally difficult. This is another reason that prompt referral for follow-up evaluation is needed.”

Tips for care, future studies

Moving forward with these survey findings in mind, McColley said it is important for those caring for pregnant people to think about the way they deliver information about newborn screening. She recommends this handout from the JAMA Network and the Baby’s First Test website for educating expectant parents.

“Many people retain information better if they hear messages on more occasions and can access more information later,” McColley said. “Clinicians who care for infants could remind parents that newborn screening test results will be available within the first weeks of life, starting at the first examination after birth, and assure that parents or caregivers receive the infant’s newborn screening test results.”

In addition to the above recommendations, clinicians should be ready to address concerns and offer support to parents with a child with an abnormal screening test, McColley continued.

“Existing supports, including nurses, doulas, lactation consultants, community health workers and other community resources could be engaged to support these families,” she said.

In terms of future studies, McColley and Heffernan highlighted the research group’s interest in “current clinician practices in counseling about newborn screening before and after birth,” parents’ social-emotional outcomes following an abnormal screening test result and newborn screening messaging/communication.

“We’re interested in the best ways to get messages about newborn screening to communities, especially to groups at risk of delayed diagnosis and treatment,” McColley said.

As a final note, Heffernan emphasized the possibilities that come with knowing how parents feel about the newborn screening process.

“This work is exciting because it centers parents’ perspectives,” she said. “If we can incorporate these perspectives into the ways we communicate with parents about the newborn screening process, I’m hopeful that this will improve those communications.”