DESTIN, Fla. — A simple mnemonic device can help providers remember to ask patients with rheumatoid arthritis about key multimorbidities driving early death, according to a speaker at the Congress of Clinical Rheumatology East .

“Sometimes we just don’t remember,” Bryant R. England, MD, PhD, of the University of Nebraska Medical Center, told attendees. “There’s so much going on in a busy clinic addressing their RA, we forget to address these things.”

“There’s so much going on in a busy clinic addressing their RA, we forget to address these things,” Bryant R. England, MD, PhD, told attendees. Image: Justin Cooper | Healio

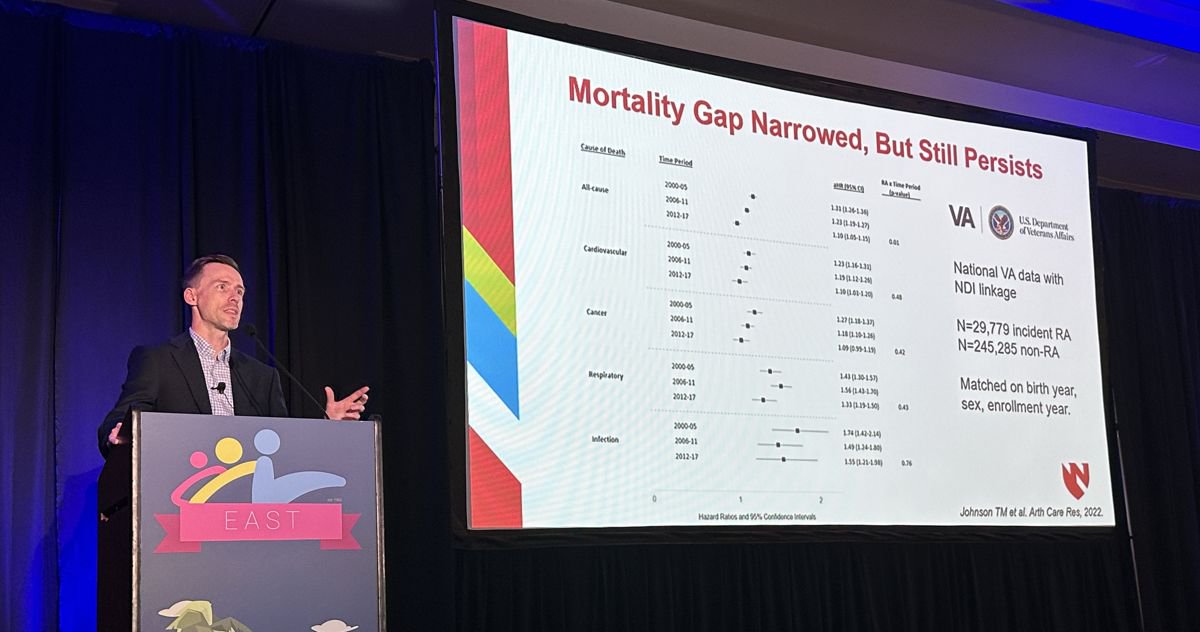

According to England, multimorbidity is a complex web in which chronic conditions influence each other and the patient. He outlined several studies that suggest patterns of multimorbidity contribute to higher disease activity and mortality among patients with RA, particularly with regard to cardiometabolic, cardiopulmonary or mental health factors.

To encourage rheumatologists to assess potential multimorbidities, England shared what he called “a simple, little, cheesy” way to remember the most important ones to ask about during each clinic visit. Based on the idea of the RA hand exam, he assigned each finger and thumb to a different pattern of multimorbidity.

“The thumb is the shortest, thickest joint. That makes us think about metabolic disease, obesity, cardiovascular disease,” England said.

At this stage, rheumatologists should ask about tobacco cessation, check lipids and give them a statin if needed, while reducing glucocorticoids and NSAIDs and encouraging physical activity, he said.

England then moved on to the index finger.

“Hold it up — it’s No. 1. And who holds up that they’re No. 1? The oncologists. They cure cancer and think they’re No. 1,” he said. “Cancer is also the No. 1 thing on many patients’ minds. So, we think about cancer screenings — lung, colon, breast, cervical, prostate, skin.”

Bryant R. England

Next was the middle finger, which England highlighted as “our longest finger.”

“A long finger means lung — long lung,” he said. “We think about tobacco cessation again. We think about asking about cough, shortness of breath. Patients are not telling their joint doctor about coughing, shortness of breath. You have to ask them about that. And then if they do have those symptoms, we have to get the right tests. It’s not a chest X-ray. It’s a high-res CT, and it’s PFTs.”

England then described the ring finger, focusing on “all sorts of nasty microbes and germs” that could be found under the ring. These should make providers think of infection, England said, and prompt discussions about vaccination or reducing or discontinuing glucocorticoids.

Arriving at the pinkie, England described it as “that little, teeny tiny finger that could break so easily.” This should make providers “think about bones, osteoporosis, getting DEXA scans, calcium, vitamin D, targeted bone therapy or reducing glucocorticoids,” he said.

Finally, England included the palm to “bring it all together.”

“That’s the mental health,” he said. “Are patients depressed? Are they anxious? Are they sleeping?”

Throughout his talk, England stressed coordination with primary care providers, who he said are better positioned to look through this holistic lens. He employed a football analogy in which PCPs are the quarterbacks of the patient’s medical care.

“Even if we’re trying to be involved with addressing these other conditions, I typically send people back to primary care,” England said. “I don’t like to do this specialist-to-specialist referral, because what you’re doing is you’re sending from the wide receiver to the other wide receiver, to the running back, to the offensive line, and really the quarterback is the one who knows what everybody is supposed to be doing.”