Ablation of the gastric fundus to reduce production of the “hunger hormone” ghrelin resulted in decreased appetite and significant weight loss among participants in a small first-in-human trial.

“Patients reported a decrease in hunger, appetite, and cravings, and an increase in control over-eating,” said senior study investigator Christopher McGowan, MD, a gastroenterologist in private practice and medical director of True You Weight Loss in Cary, North Carolina.

“They generally described that their relationship with food had changed,” McGowan said at a May 8 press briefing during which his research (Abstract 516) was previewed for Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2024.

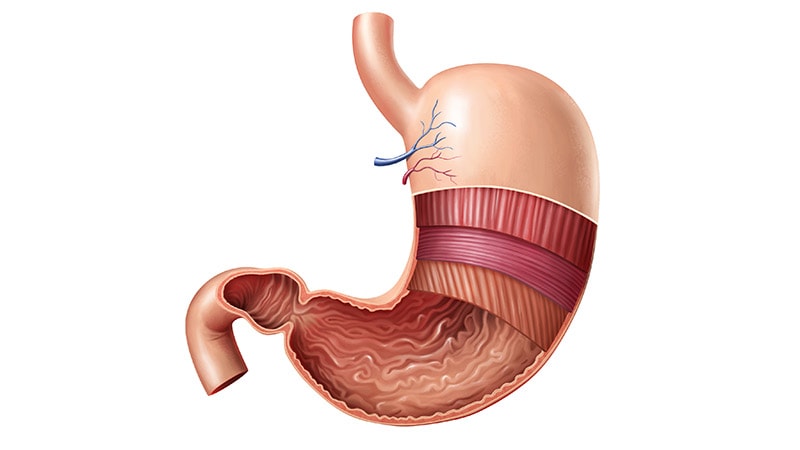

Researchers targeted the gastric fundus because its mucosal lining contains 80%-90% of the cells that produce ghrelin. When a person diets and/or loses weight, ghrelin levels increase, making the person hungrier and preventing sustained weight loss, McGowan said.

Previously, the only proven way to reduce ghrelin was to surgically remove or bypass the fundus. Weight-loss medications like Wegovy, Zepbound, and Ozempic target a different hormonal pathway, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1).

“What we’ve learned from the GLP-1 medications is the profound impact of reducing hunger,” McGowan said. “That’s what patients describe quite often — that it really changes their life and their quality of life. That’s really, really important.”

Major Findings

In the trial, 10 women (mean age, 38 years; mean body mass index, 40.2) underwent endoscopic fundic mucosal ablation via hybrid argon plasma coagulation in an ambulatory setting under general anesthesia from November 1, 2022 to April 14, 2023. The procedure took less than one hour on average, and the technique gave them easy access to the fundus, McGowan said.

Compared with baseline, there were multiple beneficial outcomes at 6 months:

- 45% less circulating ghrelin in the blood

- 53% drop in ghrelin-producing cells in the fundus

- 42% reduction in stomach capacity

- 43% decrease in hunger, appetite, and cravings

- 7.7% body weight loss

Over the 6 months of the study, mean ghrelin concentrations dropped from 461.6 pg/mL at baseline to 254.8 pg/mL (P = .006).

In a standard nutrient drink test, the maximum tolerated volume among participants dropped from a mean 27.3 oz at baseline to 15.8 oz at 6-month follow-up (P = .004).

Participants also completed three questionnaires. From baseline to 6 months, their DAILY EATS mean hunger score decreased from 6.2 to 4 (P = .002), mean Eating Drivers Index score dropped from 7 to 4 (P < .001), and WEL-SF score improved from 47.7 to 62.4 (P = .001).

Repeat endoscopy at 6 months showed that the gastric fundus contracted and healed. An unexpected and beneficial finding was fibrotic tissue, which made the fundus less able to expand, McGowan said. A smaller fundus “is critical for feeling full.”

No serious adverse events were reported. Participants described gas pressure, mild nausea, and cramping, all of which lasted 1-3 days, he said.

“The key here is preserving safety. This is why we use the technique of injecting a fluid cushion prior to ablating, so we’re not entering any deeper layers of the stomach,” McGowan said. “Importantly, there are no nerve receptors within the lining of the stomach, so there’s no pain from this procedure.”

Another Anti-Obesity Tool?

“We’re all familiar with the epidemic that is obesity affecting nearly 1 in 2 adults, and the profound impact that it has on patients’ health, their quality of life, as well as the healthcare system,” McGowan said. “It’s clear that we need every tool possible to address this because we know that obesity is not a matter of willpower. It’s a disease.”

Gastric fundus ablation “may represent, and frankly should represent, a treatment option for the greater than 100 million US adults with obesity,” he added.

It remains unclear whether gastric fundus ablation would be a stand-alone procedure or used in combination with another endoscopic weight-management intervention, bariatric surgery, or medication.

Not every patient wants to or can access GLP-1 medications, McGowan said. Also, “there’s a difference between taking a medication long-term, requiring an injection every week, vs a single intervention in time that carries forward.”

Ablation could also help people transition after they stop GLP-1 medications to help them maintain their weight loss, he said.

The endoscopic sleeve, which is a stomach-reducing procedure, is very effective, but it doesn’t diminish hunger, McGowan said. Combining it with ablation may be “a best-of-both-worlds scenario.”

McGowan reported consulting for Boston Scientific and Apollo Endosurgery.

Damian McNamara is a staffjournalist based in Miami. He covers a wide range of medical specialties, including infectious diseases, gastroenterology and critical care. Follow Damian on Twitter: @MedReporter.