Nathan Lambert , 2025-11-16 21:36:00

First, on the topic of writing, the polished, and more importantly printed, version of my RLHF Book is available for pre-order. It’s 50% off for a limited time, you can pre-order it here!

Like a lot of writing, I’ve been sitting on this piece for many months thinking it’s not contributing enough, but the topic keeps coming up — most recently via

— and people seem to like it, so I hope you do too!

It’s no longer a new experience to be struck by just how bad AI models are at writing good prose. They can pull out a great sentence every now and then, particularly models like GPT-5 Pro and other large models, but it’s always a quick comment and never many sustained successive sentences. More importantly, good AI writing feels like a lucky find rather than the result of the right incantation. After spending a long time working training these models, I’m fairly convinced that this writing inhibition is a structural limitation to how we train these models today and the markets they’re designed to serve.

If we’re making AIs that are soon to be superhuman at most knowledge work, that are trained primarily to predict text tokens, why is their ability to create high quality text tokens still so low? Why can’t we make the general ChatGPT experience so much more refined and useful for writers while we’re unlocking entirely new ways of working with them every few months — most recently the CLI agents like Claude Code. This gap is one of my favorite discussions of AI because it’s really about the definition of good writing is in itself.

Where language models can generate beautiful images from random noise, they can’t reliably generate a good few sentences from a couple bullet points of information. What is different about the art form of writing than what AI can already capture?

I’m coming to believe that we could train a language model to be a great writer, but it goes against so many of the existing training processes. To list a few problems at different stages of the stack of varying severity in terms of their handicapping of writing:

-

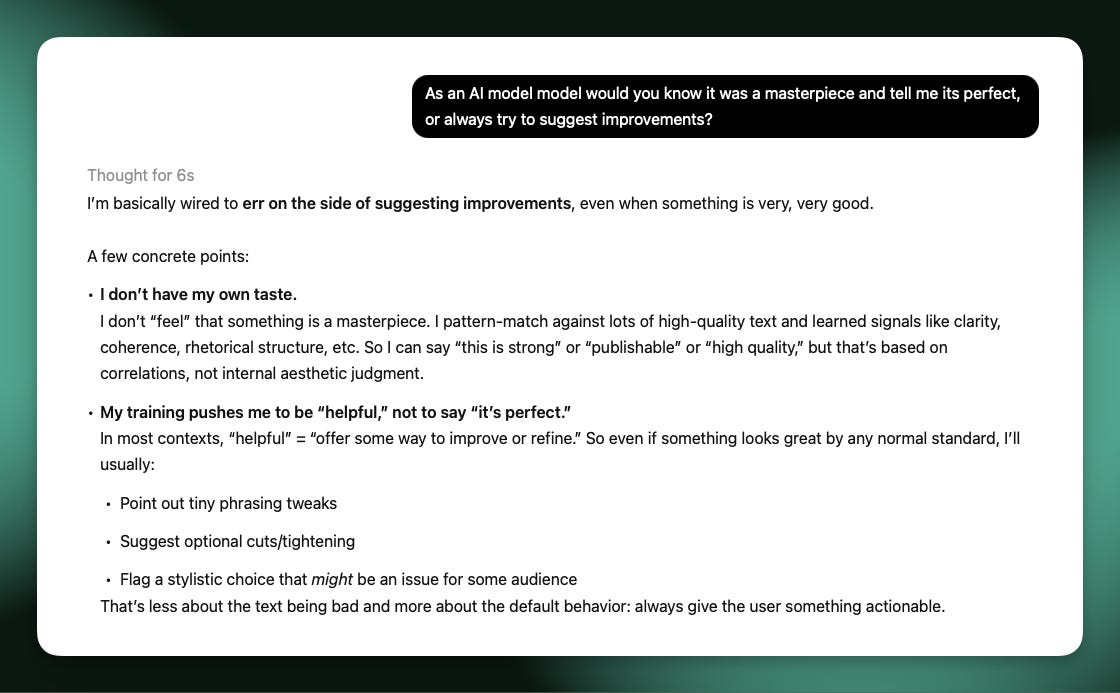

Style isn’t a leading training objective. Language models all go through preference training where many aspects from helpfulness, clarity, honesty, etc. are balanced against each other. Many rewards make any one reward, such as style, have a harder time standing out. Style and writing quality is also far harder to measure, so it is less likely to be optimized vis-a-vis other signals (such as sycophancy, which was easier to capture).

-

Aggregate preferences suppress quirks. Language model providers design models with a few intended personalities, largely due to the benefits of predictability. These providers are optimizing many metrics for “the average user.” Many users will disagree on what their preference for “good writing” is.

-

Good writing’s inherent friction. Good writing often takes much longer to process, even when you’re interested in it. Most users of ChatGPT just want to parse the information quickly. Doubly, the people creating the training data for these models are often paid per instance, so an answer with more complexity and richness would often be suppressed by subtle financial biases to move on.

-

Writing well is orthogonal to training biases. Throughout many stages of the post-training process, modern RLHF training exploits subtle signals for sycophancy and length-bias that aren’t underlying goals of it. These implicit biases go against the gradient for better writing. Good writing is pretty much never verbose.

-

Forced neutrality of a language model. Language models are trained to be neutral on a variety of sensitive topics and to not express strong opinions in general. The best writing unabashedly shares a clear opinion. Yes, I’d expect wackier models like Grok to potentially produce better writing, even if I don’t agree with it. This leads directly to a conflict directly in something I value in writing — voice.

All of these create models that are appealing to broad audiences. What we need to create a language model that can write wonderfully is to give it a strong personality, and potentially a strong “sense of self” — if that actually impacts a language model’s thinking.

The cultivation of voice is one of my biggest recommendations to people trying to get better at writing, only after telling them to find something they want to learn about. Voice is core to how I describe my writing process.

When I think about how I write, the best writing relies on voice. Voice is where you process information into a unique representation — this is often what makes information compelling.

Many people have posited that base models make great writers, such as when I discussed poetry with Andrew Carr on his Interconnects appearance, but this is because base models haven’t been squashed to the narrower style of post-trained responses.

I’ve personally been thinking about this sort of style induced by post-training recently as we prepare for our next Olmo release, and many of us think the models with lower evaluation scores on the likes of AlpacaEval or LMArena actually fit our needs better. The accepted style of chatty models today, whether it’s GPT-5, DeepSeek R1, or a large Qwen model, is a bit cringe for my likes. This style is almost entirely applied during post-training.

Taking a step back, this means base models show us that there can be great writing out of the models, but it’s still far from reliable. Base models aren’t robust enough to variations to make great writers — we need some form of the constraints applied in post-training to make models follow Q&A. The next step would be solving the problem of how models aren’t trained with a narrow enough experience. Specific points of view nurture voice. The target should be a model that can output tokens in any area or request that is clear, compelling, and entertaining.

We need to shape these base models with post-training designed for writing, just as the best writers bend facts to create narrative.

Some models makers care a bit about this. When a new model drops and people rave about its creative writing ability, such as MoonShot AI’s Kimi K2 line of model, I do think the team put careful work into the data or training pipelines. The problem is that no model provider is remotely ready to sacrifice core abilities of the model such as math and coding in pursuit of meaningfully better writing models.

There are no market incentives to create this model — all the money in AI is elsewhere, and writing isn’t a particularly lucrative market to disrupt. An example is GPT 4.5, which was to all reports a rather light fine-tune, but one that produced slightly better prose. It was shut down almost immediately after its launch because it was too slow and economically unviable with its large size.

If we follow the voice direction, the model that is likely to be the best writer relative to its overall intelligence was the original revamped Bing (aka Sydney) model that went crazy in front of many users and was rapidly shut down. That model had THOUGHTS it wanted to share. That’s a starting point, but a scary one to untap again. This sort of training goes far beyond a system prompt or a light finetune, and it will need to be a new post-training process from start to end (more than just a light brush of character training).

We need to be bold enough to create models with personality if we want writing to fall out. We need models that speak their views loudly and confidently. These also will make more interesting intellectual companions, a niche that Claude fills for some people, but I struggle with Claude plenty of times due to its hesitance, hedging, or preferred answer format.

For the near future, the writing handicap of large language models is here to stay. Good writing you have to sit in to appreciate, and ChatGPT and the leading AI products are not optimized for this whatsoever. Especially with agentic applications being the next frontier, most of the text written by the models will never even be read by a human. Good writing is legitimately worse for most of the use cases I use AI for. I don’t like the style per se, but having it jump to be a literary masterpiece would actually be worse.

I don’t really have a solution to AI’s writing problem, but rather expensive experiments people can try. At some point I expect someone to commission a project to push this to its limits, building a model just for writing. This’ll take some time but is not untenable nor unfathomably expensive — it’ll just be a complete refresh of a modern post-training stack.

Even if this project was invested in, I don’t expect the models to be close to the best humans at elegant writing within a few years. Our current batch of models as a starting point are too far from the goal. With longer timelines, it doesn’t feel like writing is a fundamental problem that can’t be solved.